Although there’s no transcript of a conversation, later events suggest that, at some point early in his tenure, former postmaster general Louis DeJoy asked why there were uniformed police circulating around USPS HQ. Many companies have security guards, usually sourced from any of a variety of private companies, so it might have seemed curious to DeJoy that the Postal Service had its own security force.

Of course, perhaps unknown to DeJoy, postal police officers, uniformed members of the US Postal Inspection Service, weren’t only stationed at public entrances to the headquarters building. They also were present in large post offices, patrolling postal property, providing valuable protection for letter carriers in high-crime areas, and supporting postal inspectors’ investigative work.

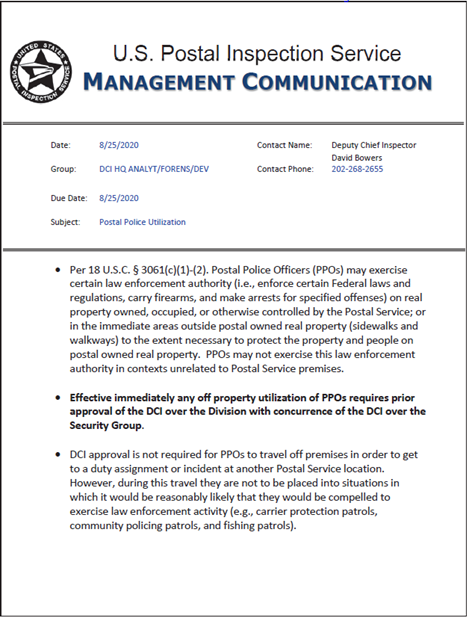

Nonetheless, eager to put his cost-reduction ideas to work, DeJoy wanted outsource postal security, reducing the role of the PPOs, confining them to USPS property, and barring them from any patrolling or other crime deterrence work farther afield. This was reflected in order issued August 25, 2020, by the Deputy Chief Inspector:

In an odd bit of counter-rationale, a consultant firm endorsed the action as a cost reduction strategy. Setting aside the value of losses not experienced because of the PPOs’ patrols’ deterrent value, the focus was instead on the opportunity to contract the protective function to lower cost private companies. Soon – and still – private security guards are at the entrances to USPS HQ; one PPO is often but not always present.

Consequences

More serious was the result of the PPOs no longer being off USPS property. As reported October 23 by FedWeek,

“Within months, robberies of mail carriers, theft of arrow keys, and large-scale mail-theft attacks surged. The system lost its feedback loop of deterrence – the invisible circuitry that once kept postal crime in check. …

“Criminologists have long known that deterrence operates on a log-linear curve: small, steady doses of visible enforcement yield disproportionately large reductions in crime, while modest withdrawals cause disorder to spike. Deterrence is fragile. Once visibility falls below a threshold, offenders sense impunity and crime multiplies.

“This isn’t conjecture. Before criminologists quantified it, the Inspection Service proved it when it created the Postal Police Force in 1970 to stop surging mail theft and robberies of letter carriers. The formula was simple: visibility equals deterrence. Low-level criminals don’t calculate probabilities; they react to what they see. A uniformed officer compresses the calculus of risk into one thought – ‘I might get caught.’

“When that perception vanished, deterrence collapsed – and mail theft, carrier robberies, and key thefts surged. Yet instead of restoring prevention, USPIS mistook paperwork for policing by focusing on post hoc investigations alone. …”

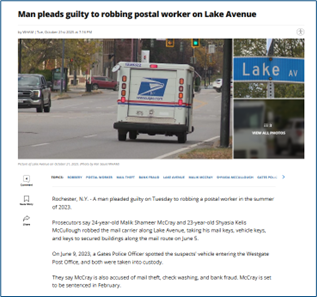

Readers need not look far to validate the statements above. Virtually any day of the week the general media – as well as postal news outlets – carry reports of mail theft, collection boxes being vandalized, letter carriers being robbed of their arrow keys, or, worse, being assaulted and, in some cases, killed. The USPIS may investigate all such occurrences, and may succeed in capturing and prosecuting the offenders involved, but such activity is obviously after the crime was committed and the associated losses or injuries inflicted.

Observers may argue whether the reported crimes would have occurred had there been a PPO in the area, or accompanying the carrier, and consultants may assert that, despite the losses and injuries, removing the PPOs from external (off-property) activities was efficient and cost-effective. Clearly, the latter claim must be set in the context of what matters to the evaluator.

Regardless, as Postmaster General David Steiner continues to examine the agency which he now leads, and review the decisions made by his predecessor in pursuit of efficiency and cost reduction, he may want to evaluate whether the curtailment of PPOs’ responsibilities, and the small savings derived from outsourcing their protective work, was really worth the true cost.